DURHAM, N.C. -- Trevon Duval was mad. Really mad. Huff-and-puff, tears-streaming-down-his-cheeks mad.

His mother, Chaka Campbell, was in the kitchen making dinner. The kitchen window overlooked the backyard of the family's home in New Castle, Del., a suburb 30 miles outside Philadelphia. The family had moved here for a better, calmer life for their children, a different world from where Trevon's parents had met in New York City. It was their dream house: A big yard, a pool, a basketball hoop in the driveway and, in the backyard, a concrete basketball court. From her perch in the kitchen, the boy's mother watched the drama unfold.

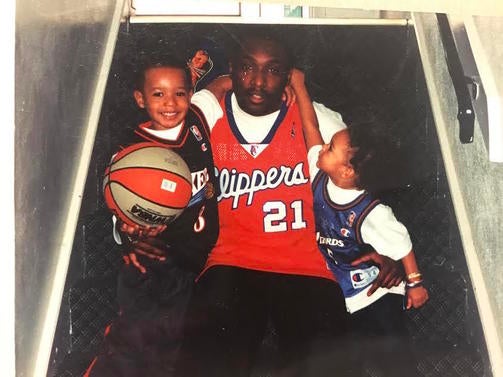

Her then-husband, Trevor Duval, had poured the concrete and built the basketball court for their oldest son. And every day, those two were on that court, doing basketball drills. Layups with either hand. Dribbling drills. Free throws. Some days, young Trevon didn't want to do the work. And on those days, his dad jawed with him. Got in his head. Made him do pushups.

This was one of those days.

Trevon, eight or nine years old at the time, walked in the back door, furious at his father. Chaka was concerned. Was her husband being too hard on the boy? Was he forcing him into a basketball life that he didn't want?

"I said, 'Son, listen: If you don't want to do this no more, just tell me so,' " Duval's mother recalled years later. "He looked at me, took a few breaths. And he said, 'Mommy, it's OK. I want to do it.' And once he said that, whenever they bumped heads, I'd just let them be."

These days, Duval is starting as the freshman point guard for a Duke team that is the nation's most talented squad. Duke is 25-6 and ranked fifth in the country going into this weekend's ACC Tournament. If Duke isn't on your short list for potential national champions, you haven't been paying attention.

And Duval, a flashy player whose game is inspired by his father taking him to New York City streetball courts and watching AND1 mixtapes together, may be the key to how deep Duke can make it in March. Duval's season has been up and down. His 3-point shooting has been subpar, at 28 percent, and there have been games where he tries to do too much and ends up having too many turnovers. Yet Duval, when he plays within himself, can become Duke's X factor, dishing assists to his talented teammates and driving down the lane like a madman. In Duke's final regular-season game, a home win over North Carolina, it was Duval who keyed Duke's comeback with six assists, two steals, a key three-pointer and, crucially, zero turnovers.

"There is the flash, and that's kind of his reputation coming in, the whole 'Tricky Tre' thing," Duke associate head coach Jeff Capel said. "The things he can do with the ball, the things he can do with his passing, his vision – you don't want to completely tone it down, but you have to steer it in the right way. He has gifts and tools, but his dad used to say this when we were recruiting him: He's raw. He's being taught certain things about the point guard position. But he can make plays that you can't teach."

Yet they were taught. CBS SPORTS HQ sat down with Duval, his parents and coaches to discuss the path that brought this young man to one of college basketball's premier programs with a game built on asphalt ideology as much as hardwood engineering.

His father was his first teacher. When Trevon, the oldest of four, was a baby, his dad would slip a Nerf basketball in the crib. At age 2, he was playing in a YMCA league; Trevon would come to games wearing headbands and Jordans, shooting jumpers over 4-year-old fools. In their old apartment, his dad would drill him on their Little Tikes hoop. Father and son would watch "Come Fly With Me," the old 1989 Michael Jordan documentary, on VHS. They also watched AND1 mixtapes, studying streetball legends like Rafer "Skip 2 My Lou" Alston and Ed "Booger" Smith, a Brooklyn streetball legend.

As Trevon grew older, his father kept pushing him. Other parents saw it. They wondered if the dad pushing the son so hard was healthy. James Johns, who coached Duval in AAU ball since sixth grade, wondered at first if the dad was crazy. Soon, he learned Trevor Duval wasn't crazy; he was driven toward a goal, and Trevon was driven toward the same goal.

"His dad's a mad scientist," Johns said. "The kid wanted it from an early age. You just saw the desire he had to be great. The family made so many sacrifices get him to be great. His dad's just a basketball junkie. He just pushes him. And anybody who has any involvement with him is required to push him at that same level."

Trevor Duval always taught his son to be a fun player – "fundamentally creative" is how he terms it. As Trevon grew older, his father pushed him to study NBA guards. Steve Nash. Derrick Rose. Kyrie Irving. James Harden. The flashy player he became melded well with Duval's Caribbean roots: His father's family is from Trinidad, and his mother grew up in Jamaica before moving to New York in elementary school.

"I always tell him, where I'm from, the era I'm from, you want to be entertaining," his father said. "You want to get fundamentals right, but you want to be exciting. You gotta add some flash to your game."

Anyway, his mother was convinced even before he was born that he was going to be an entertainer.

"It's crazy – when I was pregnant with Trevon, I was living in New York, and I was out and this Jamaican guy came over to me and touched my stomach," Trevon's mother recalled. "He said, 'I'm telling you, you're having a little boy, and he's go to be some kind of entertainer. I don't know what kind of entertainer he's go to be, but he's go to entertain people.' "

His dad pushed him to steer that entertaining nature toward basketball. Sometimes he pushed him too hard. When he was 4, the Harlem Globetrotters put on a camp in Delaware. The camp was for age 7 and up, so Trevon's dad told him to lie about his age. It wasn't like he couldn't compete; at that age, Trevon was already playing in a league for ages 8 and under.

"We'd go to the YMCA in New Castle to work out," Trevon Duval said. "My dad used to go there and play sometimes, and I'd play on the side with younger kids, but when we went there to work out, it'd be an empty gym, just me and him. I wouldn't like whatever he was saying. He'd just get on me. If I didn't want to play, if I acted like a baby, he'd say, 'Run laps.' Or, 'Do pushups.' "

"There were times when I'd be in a game and he'd talk to me too much, and I'd just say, 'Shut up, leave me alone,' " he continued. "But it all helped me come to where I am now."

There was another moment, too, when the son realized how much his father's basketball obsession was actually expressing a tough sort of love through basketball.

It was winter of Trevon's eighth-grade year. Trevon scored an invitation to a prestigious John Lucas basketball camp in Chicago. The situation seemed to call for the family cancelling the trip: A blizzard was coming. His dad's car wasn't working. And his dad was supposed to start a new job in Delaware on Monday, the day after the camp ended.

Trevon Duval didn't care. He knew his son needed this camp, the coaching it would give him and the exposure it would provide. He rented a compact car at the last minute. Starting on Friday night, the father first drove to the King of Prussia Mall in Philadelphia to buy Trevon a new pair of sneakers, red, white and blue Under Armour Spines. Then they drove down the Pennsylvania Turnpike as the blizzard came down. Trevon slept in the back seat. Through the whole night, the father drove, 13 hours straight. When Trevon woke up, they talked basketball, and they planned on how he could best showcase his skills during the weekend.

"Dad," Trevon said, "they're going to remember my name at this camp. Everyone's going to know who I am by the time we leave here."

When they got to Chicago, they didn't even check in at the hotel. They drove straight to the camp. Trevon brushed his teeth in the bathroom, washed up and got dressed.

It did become Trevon Duval's breakout weekend. It was the first time he dunked on someone. It was that weekend that rocketed him up in recruiting rankings, an ascendance that eventually led him to Duke. On the drive back, the father and the son were euphoric. They knew they were heading to something big. They knew the hard work and the butting of heads was going to pay off.

"My dad had really good interests for me in whatever I did," Duval said. "There were tough times. And it took a while to realize that. But I definitely do now."